Life in the Trenches

How Glen Elarbee took Mizzou’s offensive line from glaring weakness to shining attraction.

Glen Elarbee arrived in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, in the summer of 1998 as an undersized, lightly recruited offensive lineman. He was listed at 250 pounds in the Middle Tennessee State University media guide, and after a redshirt season, his weight ballooned all the way up to 257. Even in an upstart program that was trying to find its way as it transitioned to Division I, Elarbee was easy to miss. But when Joe Wickline was hired as the offensive line coach in 1999, he saw a potentially special player, one who was hungry to consume every last detail of his craft.

“Right off the bat, here’s one of the things I remember about him,” Wickline says. “As a coach, you go over materials, you go over concepts. Sometimes you’ll be in the gray area, and you might get away with it. And sometimes there’s a guy in the room. Well, Glen was that guy. He’d raise one eyebrow and halfway close the other eye, and you’d know right then you’d better be on your toes when you had the chalk in your hand because he was going to test you. But he did it in a way that was always constructive. He really wanted to know. He’s truly a student of the game.”

In his first two seasons, Elarbee appeared in 12 games as a reserve, and at the beginning of his junior year, now tipping the scales at a robust 275 pounds, he earned the starting job at center. He never gave it back. The Blue Raiders finished 8-3 in 2001 and won the Sun Belt Conference championship. Playing a schedule that featured games against three SEC teams, MTSU ranked fifth in the country in total offense, seventh in rushing offense and ninth in scoring. Elarbee made 23 consecutive starts and earned all-conference honors in each of his final two seasons.

“He was an amazing overachiever,” recalls Wickline, who now is an assistant at West Virginia. “He played with a big chip on his shoulder.”

It is quite the success story. So we probably shouldn’t be surprised that in his first year as the offensive line coach at Missouri, Elarbee took a unit that was arguably the Tigers’ biggest weakness in 2015 and turned it into one of its greatest strengths. In the season before he arrived, Mizzou ranked 125th in the country in total offense, allowed 88 tackles for loss and scored just 15 touchdowns — they didn’t even reach the end zone in five games. Last year the Tigers led the country with just 35 tackles for loss — their per-game average was the best in the country dating to 2005 — and led the SEC in total offense while allowing a conference-low 14 sacks. They were the only team in the conference to produce a 3,000-yard passer, a 1,000-yard receiver and a 1,000-yard rusher. Most amazing is that the yards and points were piled up behind a line that was breaking in four new starters and entered the season with a combined three career starts. Although Mizzou finished 4-8, Elarbee was one of 40 nominated for the Broyles Award, which honors the top assistant in college football.

Elarbee has deep roots in the South. He played high school ball in the sleepy Georgia town of Carrollton, about 50 miles west of Atlanta. He earned a bachelor’s degree in mathematics (and then a master’s in sports management) but as his playing career wound down, he had such a passion for the game that he wanted to stay connected to it. Coaching seemed like a natural fit. He worked for two years at his alma mater as a graduate assistant and the tight ends coach, then was a grad assistant at LSU and Oklahoma State. He returned to coach at hometown West Georgia for a couple of seasons. As a full-time assistant at MTSU and Houston, he matched wits with Barry Odom, who at the time was the defensive coordinator at Memphis. Elarbee saw Odom as a brilliant defensive mind, so when their paths crossed in 2013 at a high school clinic and recruiting event in East Texas, he made it a point to introduce himself.

“He was way ahead of the curve on that side of the ball,” Elarbee says of Odom. “I remember going up to him and saying, ‘I have a tremendous amount of respect for you and what you’re doing.’ Some of the three-down [linemen] stuff he was doing at Memphis was making my life a nightmare. We talked a little bit about football. He was awesome, a good dude, open. We talked some schematics.”

Three years later, after Elarbee’s second season at Arkansas State, the two were talking about a job. Having grown up in SEC country, Elarbee had always dreamed of coaching in the conference. He fondly remembered the trips he had made to Columbia as an assistant, so much so that he envisioned Mizzou as a potential landing spot. He was confident his wife, Holly, and their young son would embrace Columbia as heartily as he had. Of course, knowing for whom he’d be working was no small factor.

Elarbee is a humble, self-deprecating individual with an admitted deadpan sense of humor, so it’s no surprise that he’s quick to deflect the credit for the dramatic turnaround his unit made. He praises the work ethic and commitment of his players. He gives a nod to offensive coordinator Josh Heupel and graduate assistant Jon Cooper. He mentions the benefits gained from practicing against an uber-talented defensive line. (“They give me fits every day”). He notes what a valuable resource Odom is — how he might walk in on a Sunday morning and scribble a scheme on the board, suggesting how the defensive coordinator of an upcoming opponent might be plotting.

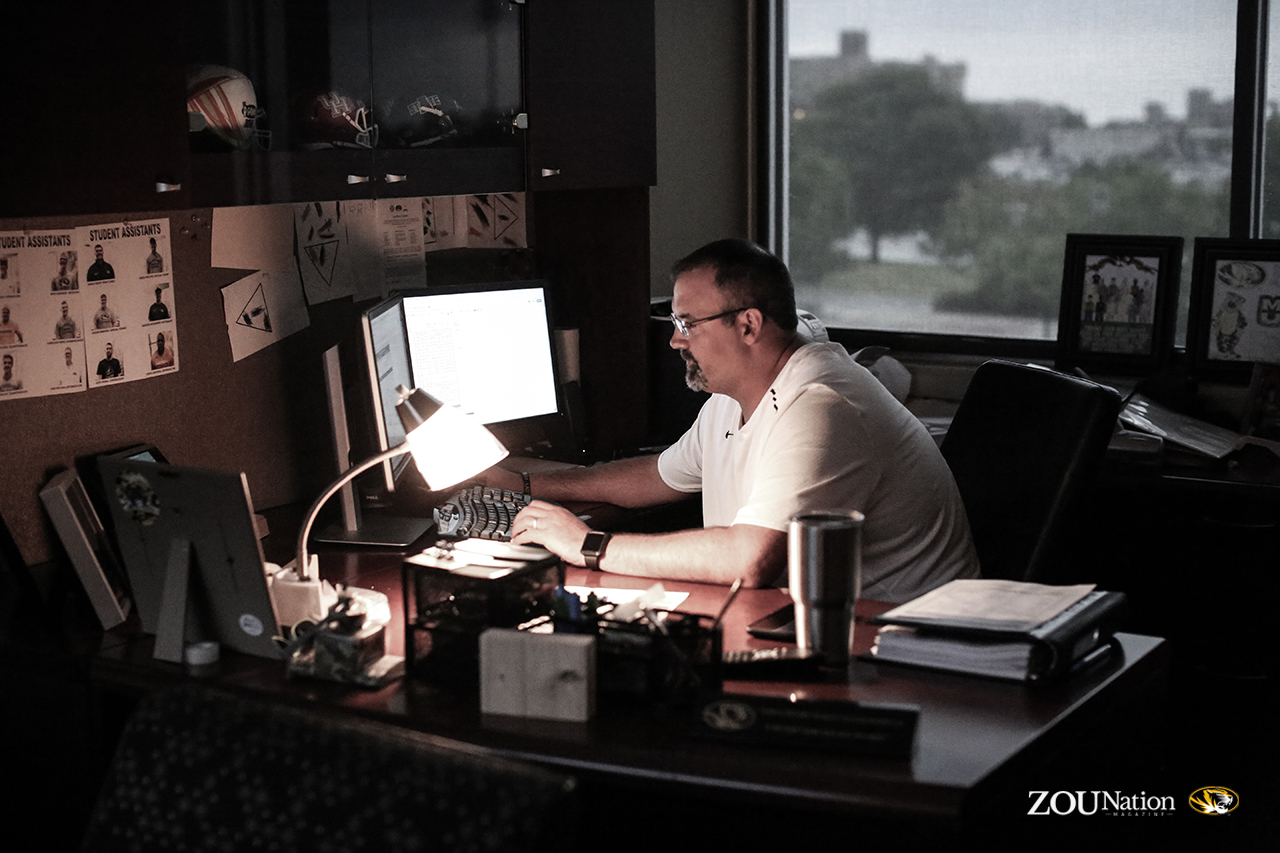

Yet it’s impossible to dismiss the work of the 37-year-old Elarbee. So just where did he begin with the reconstruction?

“You always start in the same place, just what we want to be about,” he says. “I tried to talk to the guys about five things we want to believe in. The first is being tough and physical. Then we want to give great effort in everything we do. The third goal we have at the start of spring practice is to play smart and intelligently. Then we hone technique. When we get those four things accomplished, we try to be a tight unit, love each other and want to hang around each other.”

Depth was a concern in the spring of 2016, yet Elarbee saw the problem as an opportunity. “The biggest asset was that those guys got a lot of reps,” he says. “They had to soak up a ton of them. The more you do something, the better you get. And it gave them some versatility to play the left side, the right side, inside, outside.”

Then there was the issue of tempo. Mizzou played as fast as any offense in the country last season. Heupel’s no-huddle attack might have been daunting for an assistant who was teaching and shuffling players and learning the nuances of a new system right along with his troops, but Elarbee was unfazed by it all. “I’m used to having to limit calls and communication and playing the game fast,” he says. Adds Wickline, “I know everybody talks about tempo these days, but I’m here to tell you, we were doing that a long time ago.” As the center, Elarbee had to call out assignments at the line of scrimmage, make a shotgun snap and execute his block, all in the span of a few seconds. He can share those experiences, along with the knowledge he has acquired during his 15 years as a coach. He has played and worked under some of the best offensive minds and at some of the top programs in the sport. Larry Fedora, now the coach at North Carolina, was the offensive coordinator at MTSU. Elarbee worked as a graduate assistant under Les Miles when LSU won the national title in 2007 and for Mike Gundy at Oklahoma State, where he reconnected with Wickline, his former position coach. “He really changed who I was,” Elarbee says of Wickline. “He helped me become a man. He taught me a ton about football and life.”

A 35-year coaching veteran, Wickline got an up-close look at his protégé’s work-in-progress when Mizzou and West Virginia opened their 2016 seasons last September. Although the Mountaineers prevailed, the mentor came away impressed. “I was in the SEC for a number of years, and I’ve watched a lot of cross tape,” Wickline says. “I watched their guys progress, and it really didn’t surprise me. He’s fundamentally sound. He communicates extremely well. His players will like him. He’s got a great deal of passion. He doesn’t have a giant ego.”

In other words, Elarbee is a reflection of the player Wickline coached in Murfreesboro: an old-school offensive lineman who would never be outworked and whose love for the game rubbed off on others. It can be contagious. Elarbee coaches without a whistle, preferring instead to say tweet, tweet to signal the end of a drill. He considers the prospect of a whistle dangling from his lips an opportunity lost, a chance missed to communicate with his players. To teach — isn’t that what coaching is all about?

As a player at MTSU, Elarbee owned three pet piranhas. Of course he did. Because nothing screams offensive lineman like a pet piranha. But three? “Can’t have one or two,” he explains. “Not healthy for them.” Or him, as it turns out. On the eve of a game against Tennessee, Elarbee sliced his left hand while cutting up meat to feed his prized possessions. The good news: The gash was on his non-snapping hand. He taped the wound and didn’t miss a down. As a coach, he may have head-butted a chair or bumped a meeting-room wall — “I’m not sure I’m supposed to divulge those secrets,” he quips — but it was only to drive home a point. Old school, no doubt about it. At the same time, he keeps pushing ahead, searching for a tweak that might be as subtle as an adjusted hand placement — ever in search of an edge, always trying to get better.

“As a coach, you never feel you’re far enough ahead,” Elarbee says. “You always see that next step you need to take. It’s hard to look back and say, ‘We were here,’ when all you want is to keep looking forward.”

Then allow us: Suffice it to say that the Missouri offensive line is in a much better place than it was a year ago.

Photos: Caroline Hall