The Legend of Norm

Twenty-five years after he launched Coaches vs. Cancer, Norm Stewart's achievements span well beyond the Missouri hardwood.

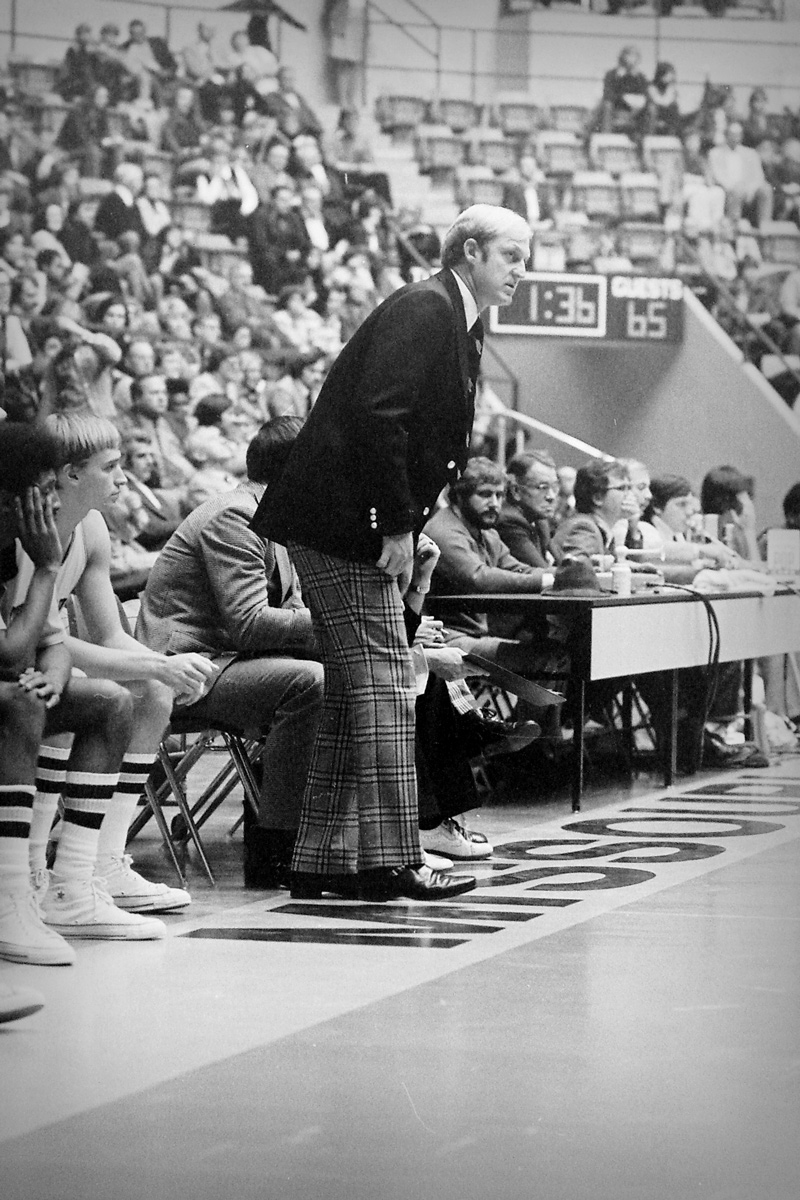

“For the first time in 32 years, the University of Missouri will have a new men’s basketball coach.” That statement, printed atop a 1999 press release by the athletic department, had a head-tilting effect for those who couldn’t imagine a Missouri basketball program without one legendary man on its sidelines. The career of a fascinating and prominent figure, Coach Norm Stewart, was ending.

He stood at the podium announcing his departure, focused and determined. His thin blonde hair had faded to gray since his early days in the Hearnes Center. “I was sitting in Lawrence in January,” he told reporters. “And the fans were chanting my favorite conference chant: ‘Sit down, Norm.’ So, I said to myself, I think I will.” This was 18 years ago.

The Commitment

Ten years prior to his retirement, things changed. After his diagnosis and treatment of colon cancer during the 1988-89 season, Norm Stewart had defeated cancer and took time to heal. He began traveling with his best friend, his wife Virginia — the two are the ultimate team. And soon enough, after he returned to his Missouri roster, he made it his mission to defeat the deadly disease for others. This time, on his own terms.

In the fall of 1993, Coach Stewart and Jerry Quick of the American Cancer Society took their 3-Point Attack fundraising efforts national. Coaches vs. Cancer was born, and just as he did with his players, Stormin’ Norman would see it raised correctly. Now in its 25th year, the program leverages the community involvement, personal experiences and nationwide platforms of basketball coaches to raise cancer awareness and funds. It’s the sole charity represented by the National Association of Basketball Coaches, and today, more than $110 million has been raised for the ACS through Coaches vs. Cancer.

“Those of us who have had the opportunity to coach this sport at a high-profile level should be very appreciative of all the things we have gained from the sport,” says Fran Fraschilla, longtime Coaches vs. Cancer supporter, studio analyst at ESPN and former collegiate coach. He, as so many others at the time, admired the coaches who had come before him. They followed the Missouri man’s lead. “We’re blessed to be involved in such a great game, and to be able to give back, to raise money in the fight against cancer, is an absolute no brainer.”

Fraschilla was a young coach with the Manhattan College Jaspers when Stewart nationalized the organization. At that time, Oklahoma head coach Lon Kruger was only on his second team out of five that he would eventually lead to the NCAA Tournament. Kruger has been a fervent supporter of the cause ever since.

“[Coach Stewart] took the lead. And at that point, he didn’t know what his prognosis was in the long run,” Kruger says. “A long-time survivor now, with his leadership, Coaches vs. Cancer was developed.” Most are well aware of Kruger’s accomplishments leading five programs to the NCAA tournament; the same effort is given in his endeavors to eradicate cancer. In 2007, Kruger began the Coaches vs. Cancer Las Vegas Golf Classic, at which 20-25 coaches gather for a weekend of fundraising. The event raised more than $2 million.

“Our coaches and the people involved have been tremendous, and that’s the greatest satisfaction,” Norm Stewart says. “Look at the Final Four [in 2015]. All four of those guys — Boeheim, Kruger, Jay Wright, Roy Williams — all of them are just huge with [the organization].”

Wright is a part of the program’s Philadelphia chapter, one of the top fundraising groups in the nation. Boeheim will celebrate the 19th year of his BasketBall gala. And Williams, through personal efforts and his Fast Break Against Cancer sit-down breakfast has raised more than $2.3 million. Williams, Boeheim and Kruger have all received the program’s Champion Award. For these reasons, Coach Stewart is quick to focus on those who have worked hand in hand, voluntarily, forgetting all rivalries that might exist, to follow his lead across the country.

Missouri’s “Band-Aid Man,” Derrick Chievous, a star player of Coach Stewart’s after the Sundvold and Stipanovich era, was once accepting an award. For what, Coach Stewart can’t recall. Maybe for his role in “The Cats From Ol’ Mizzou” rap video. Maybe not.

“He said, ‘There could be a lot of names on this award. But since it’s got mine on it, I’m gonna keep it,’” Coach Stewart remembers. “That’s the way that Coaches vs. Cancer has played out for me. My name’s on it, but the other people are the reason it’s evolved. They keep it working and make it so strong.”

Moving Forward

Just as the Missouri coach had once done, Jim Boeheim also proved that being diagnosed and defeating cancer was no reason to back away from a coaching position. It was instead grounds for a more meaningful, motivational journey. Boeheim had surgery for prostate cancer in the fall of 2001. His Syracuse Orange won the national championship the next season. And since its inception, the Jim and Juli Boeheim Foundation’s BasketBall has raised more than $6.5 million for cancer research.

“I just think you appreciate that you were able to get through it, and I talk about it all the time: The importance of getting checked often and detecting it early. It’s the best way to beat cancer,” Boeheim says. Both coaches are ardent advocates of early detection. For obvious reasons.

“Everyone always asks, ‘What can I do?’” Coach Stewart says. He’s very adamant. “Do what you can do. If you can give money, give money. But if you have a friend, and they need to go to a doctor, pick them up and take them. If someone wants to talk about something, talk with them. Remind everybody to go take their tests. Do the little things.”

The little things seem to come together for Coach Stewart. There’s a fire and charm to his style. He is one school’s spirit and one state’s magic. But his loyalty to both his team and the Coaches vs. Cancer program has made him a celebrated figure nationally. It’s because of Coach’s stubbornness and toughness, says Fraschilla, that he’s found so much success on and off the court — the toughness to fight and beat the disease and the stubbornness to not let it get him down. It’s the way he coached; what’d you expect? “His teams were always hard-nosed, and in order to get that way, you have to have a stubborn coach who’s not going to let the level of intensity of his team slip at all,” Fraschilla says. “And that’s Norm to a T. He is the ultimate competitor, but there’s a compassionate side that I’ve seen, and from a guy who’s supposed to be so tough, that’s heartwarming.”

A few years back, Coach Stewart invited Fraschilla to his Coaches vs. Cancer golf outing. It was scheduled on his 25th wedding anniversary. Fran told his wife it was hard to turn down Coach Stewart — as it is for most — but he would decline the invitation if she requested. “She said ‘Of course not. You go and certainly help Coach out, and we’ll celebrate our 25th when you get back,’” Fraschilla says. “He and Virginia sent my wife a beautiful bouquet of flowers that day. Typical Norm.”

At the time of his departure, Coach Stewart was 62 years old, and his all-time 731 career victories were behind only Bob Knight, Ray Meyer, Phog Allen, Ed Diddle, Henry Iba, Adolph Rupp and Dean Smith. Every man on that list is synonymous with the word Legend. In 1999, Coach Stewart had been involved as a player, assistant or head coach in half of the games that Missouri had played since the beginning of its program. Let that sink in if it hasn’t already. Fifty percent.

There were the eight Big Eight Conference regular-season championships, the six Big Eight Conference post-season tournament titles, 16 NCAA Tournament appearances, Coach of the Year awards, 17 seasons with 20 or more wins and 634 wins at Missouri — far and away the most in school history.

But ask Coach Stewart for a statistic that stands out to him, and he’ll tell you this story. There was a woman who once worked for him during his late years at Missouri. As a child, this woman was diagnosed with leukemia. “At that time, one of 17 kids survived,” he says. “Today, it’s just the reverse. Sixteen out of 17 survive.” Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia is the most common childhood cancer, and according to St. Jude, ALL survival rates went from 4 percent in 1962 to 94 percent today. A man with tireless intensity and a bit of a knack for on-court controversy views his career through the lens of impacting others.

“I think it was Emerson who said it’s very difficult to help somebody without helping yourself more. That’s exactly what happened here,” Coach Stewart says.

The All-American from Shelbyville, Missouri, is a legacy, and legacies survive. They survive through the tales of a storied career, and through vehement efforts to continue a fight against cancer for those beyond him. And it’s his legacy that we stand to applaud.

Photos courtesy of Mizzou Athletics